William James

Nov 09, 2008William James is a great figure, historically important as a philosopher (pragmatism and radical empiricism), a student of religion (au...

Russell Goodman, who was our guest a couple of weeks ago, for our episode on William James sent the following remarks as a follow up to our on-air conversation. They are posted here with his permission.

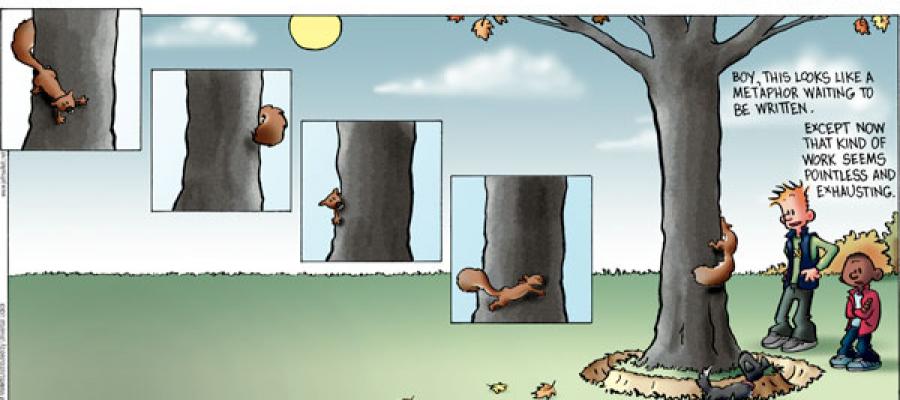

I wanted to comment on that squirrel going around the tree story with which James opens the second chapter of Pragmatism. It's a great story, but it seems, from my experience, to itself provoke as much disagreement and puzzlement as the squirrel and the man themselves do.

At first blush, it seems like a good verificationist story- a dispute about two terms or hypotheses that have the same empirical consequences. James's point would be then be that the dispute is idle (as you put it in your introduction, the campers are “arguing about nothing.”) This seems to be James's conclusion in the second paragraph, where he writes: “If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle.” That's fine, and this statement fits Peirce's example (in “How to Make our Ideas Clear”) of a cup of wine that is allegedly Christ's blood but gives all the signs of just plain wine.

But James's conclusion does not fit what he says in the first paragraph, where the point is NOT that there is no “practical difference” between the cases but rather that if one makes the distinction between two senses of “going around” (i. e. passing north of, east of, south of, west of, vs. facing the belly, then the side, then the back, then the other side of the squirrel) there is no need for disagreement. That's because each sense determines a DIFFERENT, empirically verifiable set of consequences, either for the man himself (if he can catch sight of the squirrel's belly, etc, it being a narrow tree) or certainly for the observers, who can tell whether the man is facing the squirrel's back or belly (is the squirrel standing?) or merely circling a squirrel who keeps his belly facing the man.

So, James misinterprets his own example as one in which there is no practical difference between the two hypotheses, when there actually is. In either interpretation however, the example is meant to furnish a picture of traditional philosophy, as (in the words of one of James's heroes, George Berkeley) raising a dust and then complaining that one cannot see. In this guise pragmatism is a critical philosophy or therapeutic philosophy, freeing us from pseudo problems. There's also a positive side (e. g. his 'humanistic epistemology') that the example doesn't seem to exemplify.

Another puzzling thing about James's example is the question of what it has to do with pragmatism, or why we need pragmatism to tell us this? As James points out, the idea of making a distinction when we encounter a (seeming) contradiction is an old one in philosophy. It's a funny idea to invoke at the beginning of a chapter where one expects to learn about what is distinctive about pragmatism.

From years of teaching this chapter I've learned not to start with the squirrel example, but to pass to other points he makes in this really quite amazing piece of writing. Last spring I gave a seminar on the chapter in North Carolina and we had a very lively discussion about the squirrel example for most of an hour, with people disagreeing about whether James really did misinterpret his own example! We didn't get much further however. What do you think?

Comments (6)

Guest

Friday, January 2, 2009 -- 4:00 PM

Like the "baldness" paradox used in skepticism, isLike the "baldness" paradox used in skepticism, isn't this puzzle a result of the innate ambiguity of language being forced into mathematically pure relationships? If "around" is defined clearly enough, the puzzle is resolved, just as if baldness is defined clearly enough then a single plucked hair can turn a head bald. We remain unsatisfied, not because the logic is off, but because the language is. Language cannot be handled so prescriptively, and we feel this instinctively. Skepticism reminds us of the unavoidable mess of using plastic language with fixed logic.

Guest

Monday, January 12, 2009 -- 4:00 PM

Yes, James does seem to be confounding a number ofYes, James does seem to be confounding a number of issues in that lecture.

His resolution of the squirrel dispute (?Which party is right,? I said, ?depends on what you practically mean by ?going round? the squirrel?) looks more like linguistic analysis than anything else, and his description of of the ?pragmatic? principle in the second paragraph as ?If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle? sounds more like a version of positivism.

It is only later in the piece that he identifies pragmatism with the kind of provisionalism that most scientists take towards their theories as being useful pro tem until they need to be refined in order to accommodate further observations ?less as a solution, then, than as a program for more work, and more particularly as an indication of the ways in which existing realities may be changed?.

Guest

Tuesday, March 3, 2009 -- 4:00 PM

100% agreement. Very confusing, not enlightening100% agreement.

Very confusing, not enlightening story. Does not make the point.

Guest

Wednesday, April 1, 2009 -- 5:00 PM

"So, James misinterprets his own example as one in"So, James misinterprets his own example as one in which there is no practical difference between the two hypotheses, when there actually is."

Uhh, no. He does not.

Everyone is harping on James' statement that "If no practical difference whatever can be traced, then the alternatives mean practically the same thing, and all dispute is idle."

But you completely ignore the VERY NEXT SENTENCE!

"Whenever a dispute is serious, we ought to be able to show some practical difference that must follow from one side or the other?s being right."

Neither of these statements is addressed specifically to the squirrel example. BOTH may apply, depending on how much importance you attach to the question. THAT is the real point here.

Guest

Saturday, August 14, 2010 -- 5:00 PM

Can't say that I totally agree. The squirrel exampCan't say that I totally agree. The squirrel example was rather interesting though.

Harold G. Neuman

Tuesday, October 5, 2010 -- 5:00 PM

It is called a tautology, I believe. But, then agaIt is called a tautology, I believe. But, then again, it cannot be a tautology unless it is a) obviously so, with or without outside corroboration or b)two or more symbionts within the closed system agree that it a tautology. Inasmuch as I am not a symbiont within this closed system and do not know of the parable of the squirrel example, I can only go dancing in the dark. No worries though. I was never terribly impressed by William James anyway. Nor by Joseph Campbell for that matter. More modern thinkers get my attention---when they have something new to say.