Perhaps the most remarkable (and, for many, alarming) political event in 2015 has been the rise of Donald Trump. At first, many people thought of Trump as an amusing sideshow. Over the months, mass-media talking heads (and also lots of my philosopher friends) kept repeating that there’s “no chance” of Trump getting the republican nomination, and therefore that there’s “no chance” of his becoming president of the United States. After each of his inflammatory statements, they declared that this time Trump has “gone too far” and predicted his downfall. But instead of fading away, he’s now more prominent than ever, and is doing better than all of his rivals.

If you can’t understand how someone like Trump can garner so much support, you probably have some misconceptions about how political salesmanship works. In what follows, I’m going to take a look at political rhetoric from the perspectives of two giants of the Western intellectual tradition, Socrates and Sigmund Freud, and then from the perspective of the psychoanalyst-philosopher Roger Money-Kyrle, a thinker who is not as well known, but whose take on propagandistic political speech is stunningly useful.

Let’s kick off with Socrates. In the Gorgias, a dialogue written down by Plato around 380 BC, Socrates likens political rhetoric to junk food. Politicians, he claims, are more like pastry chefs than they are like physicians. They cook up sweet illusions rather than serving the public good. “Pastry baking has put on the mask of medicine,” he remarks, “and pretends to know the foods that are best for the body, so that if a pastry baker and a doctor had to compete in front of children, or in front of men just as foolish as children, to determine which of the two, the doctor or the pastry baker, had expert knowledge of good food and bad, the doctor would die of starvation.”[1]

There’s certainly something to be said for Socrates’ diagnosis. There’s no question that politicians often pander to our vanity and self-interest. But there’s also something wrong with it—at least when applied to modern-day politics. It’s simply not true that only “foolish” people swallow political hype. Case in point: Martin Heidegger and Gottlob Frege, the two most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, were among the most intelligent, highly educated, and reflective people around at the time. They were also ardent fans of Adolf Hitler—as were many other European intellectuals. Moreover, many prominent Nazis were highly educated. Hitler’s propaganda minister Josef Goebbels had a Ph.D. (in literature) from the University of Heidelberg, and eight of the sixteen men sitting around the table at the 1942 Wannsee Conference, where the horrific fate of Europe’s Jews was sealed, possessed doctoral degrees.

As these examples make clear, neither education nor intelligence safeguard one against the corrosive effects of political illusions. In this connection, it’s helpful to turn to the work of Sigmund Freud—in particular, his 1927 book The Future of an Illusion. Although it’s mainly about the psychology of religion, Freud’s book also sets out a general account of illusion that’s useful for making sense of the power of political rhetoric.

Freud defines illusions as beliefs that we adopt because we want them to be true. We usually think of illusions as false beliefs, but Freud rejects this view and argues that illusions can be true as well as false. He argues that what makes a belief an illusion has nothing to do with the degree to which it accords with reality and everything to do with its psychological causes. This is a subtle idea, so maybe an example will make it clearer. Suppose that (1) Joe wants to be the best looking guy in the room, (2) all of the evidence suggests that Joe is the best looking guy in the room, and (3) Joe believes that he is the best looking guy in the room. If (3) is true and is caused by (1), then—according to Freud—(3) is an illusion even though (2) is true. Of course, it would also be an illusion if (2) was false.

Freud argues that religious beliefs are illusions because they are “fulfillments of the oldest, strongest and most urgent wishes of mankind.” His point is that our lives are fragile, bounded by death, vulnerable to disease and tragic happenstance, and subject to the pain, injustice, and cruelty that we dish out to one another. He thinks that we are drawn to religious beliefs as an antidote to our ultimate helplessness in the face of these harsh realities.

Freud goes on to say that our position in the world, and the religious response to it, is like that of a young child who looks to a powerful parent for protection. “As we already know,” he writes, “the terrifying impression of helplessness in childhood aroused the need for protection – for protection through love – which was provided by the father and the recognition that helplessness lasts throughout life made it necessary to cling to the existence of a father, but this time a more powerful one.”[2]

There are clear links between Freud’s take on religion and the psychological forces that are at play in the political sphere. Politics is a response to human vulnerability—especially the vulnerability arising from our dependence upon others. Our deepest hopes and fears permeate the political arena—including those that underpin the yearning for a Higher Power—and this makes us susceptible to political illusions.

Thinking about political speech using Freudian theory yields deeper than the one that Socrates left us. Whereas Socrates makes derogatory remarks about men who are as foolish as children, Freud offers compassionate insight into the terrors of helplessness and the longing for an omnipotent parent. And whereas Socrates describes politicians as having a knack for flattery, the Freudian account explains the potent attraction of those who promise to deliver us from our own worst nightmares.

As compelling as it may seem, the Freudian story is incomplete, for two main reasons. First, it doesn’t say anything about the rhetorical means that politicians use to achieve their ends. Second, it doesn’t give us a handle on why political rhetoric emphasizes insecurity and failure at least as much as security and success. These two gaps are easy to fill. Politicians manipulate our attitudes by arousing our anxieties and then offering us illusions as a way of escaping from them.

This is all very general. To get down to the nitty-gritty, it’s helpful to draw on the insights of the British psychoanalyst Roger Money-Kyrle. During the 1920s Money-Kyrle left England, where he was working on his Ph.D. in philosophy at Cambridge University, to spend four years in Vienna undergoing psychoanalysis with Freud pursuing his philosophical research under the guidance of Moritz Schlick, the leader of the Vienna Circle. During this period, he visited Germany and went to a rally where Hitler and Goebbels spoke. It left a deep impression on him.

Money-Kyrle gives a vivid description of the rally in his 1941 paper “The Psychology of Propaganda.”

“The speeches,” he wrote, “were not particularly impressive. But the crowd was unforgettable. The people seemed gradually to lose their individuality and to become fused into a not very intelligent but immensely powerful monster” that was “under the complete control of the figure on the rostrum” who “evoked or changed its passions as easily as if they had been notes of some gigantic organ.”[3]

For ten minutes we heard of the sufferings of Germany…since the war. The monster seemed to indulge in an orgy of self-pity. Then for the next ten minutes came the most terrific fulminations against Jews and Social-democrats as the sole authors of these sufferings. Self-pity gave place to hate; and the monster seemed on the point of becoming homicidal. But the note was changed once more; and this time we heard for ten minutes about the growth of the Nazi party, and how from small beginnings it had now become an overpowering force. The monster became self-conscious of its size, and intoxicated by the belief in its own omnipotence…. Hitler ended…on a passionate appeal for all Germans to unite.[4]

Observing Hitler and Goebbels in action led Money-Kyrle to the idea that for political propaganda to work, propagandists have got to convince their audience that they need to be saved from a terrible fate. The first step is to elicit a profound sense of depression—the feeling that the future is bleak, and that this situation is their fault. The next step is to drum up a paranoid sense of fear and hate in the audience by convincing them that they are under threat from powerful external enemies and insidious internal ones. Once they’re thoroughly marinated in feelings of helplessness, and reduced to a position of infantile dependence, the skillful propagandist offers himself or his cause as the straight and narrow path to salvation: “He is all-powerful and must protect them. He is their conscience; and what he says is inevitably right.”[5]

Now, consider Donald Trump’s speech of June 16, 2015—the speech in which he announced his bid for the Republican nomination—in light of Money-Kyrle’s analysis. He begins by eliciting feelings of depression and loss. “Our country is in serious trouble,” he intones, “We don’t have victories anymore. We used to have victories, but we don’t have them. When was the last time anybody saw us beating, let’s say, China in a trade deal? They kill us…. They’re laughing at us, at our stupidity. And now they are beating us economically.”

Having created a gloomy atmosphere, he transitions to the paranoid mode, representing good Americans as innocent victims of predatory outsiders.

When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best…. They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists…. It’s coming from more than Mexico. It’s coming from all over South and Latin America, and it’s coming probably — probably — from the Middle East. But we don’t know. Because we have no protection and we have no competence, we don’t know what’s happening.

Next, the bringer of bad news unveils his panacea. Salvation is at hand. The dangers will be banished. The problems will be solved.

Now, our country needs…a truly great leader, and we need a truly great leader now. We need a leader that wrote “The Art of the Deal.” We need a leader that can bring back our jobs, can bring back our manufacturing, can bring back our military, can take care of our vets. Our vets have been abandoned…. We need somebody that can take the brand of the United States and make it great again.[6]

After repeating the first two movements a couple of times, driving his audience to a crescendo of enthusiasm (chants of “We want Trump” and “Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump, Trump”), he concludes, “Sadly, the American dream is dead. But if I get elected president I will bring it back bigger and better and stronger than ever before, and we will make America great again.”

Over the next year, we Americans are going to be inundated with political rhetoric. I hope that the insights offered by Socrates, Freud, and Money-Kyrle will help you to resist political illusions, interrogate your own preferences, and become more discerning consumers of political speech; not just the speech of those politicians whom you oppose, but also, perhaps most importantly, of those whose political rhetoric captures your sympathies.

[1] Plato, Gorgias (1987) Translated by Donald J. Zeyl. Hackett: Indianapolis, p. 25.

[2] Freud, S. (1964) “The Future of an Illusion,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Vol. 21. London: The Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis, p. 30.

[3] Money-Kyrle, R. (1978) “The Psychology of Propaganda,” In The Collected Papers of Roger Money-Kyrle. Strath Tay, Perthshire: The Clunie Press, pp.165-66

[4] Ibid., p. 166

[5] Ibid., p. 171

Comments (5)

Gary M Washburn

Monday, January 4, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

As usual, Plato isAs usual, Plato is misrepresented. In Gorgias he was laying out the form of the analogy, the fundamental structure of mind, as difference in the context of the same, as differentiation in the context of replication. Propaganda is "coherentism", promoting the false impression that what does not fit the coherentist structure cannot be meaningful at all. All the propagandist needs to do is to define terms by which all alternatives get brought into its paradigm, and all else is incoherent. It is nothing more than the prejudice that all discourse must resolve itself in agreement, and that, therefore, what cannot converge into a unified paradigm must be incoherent and dismissed tout court. The simplest example is the term "atheist" or "infidel", which denies the alternative any means of expression that does not assert and affirm the very term it tries to refute.

Freud was hardly a genius, except as a propagandist of his own brilliance, despite the absurdity of his thesis. Edward Bernays pulled off the most effective propaganda stunt in history, hiring a gang of well-dressed and good-looking young women to march in a suffragette parade while smoking, creating an association of cigarettes with feminism that has lasted to this day. The most perspicuous book on the subject should have been mentioned in the set-up above, but I cannot remember the author or title, so I will try to describe it and perhaps the more astute visitor will recognize it. I think it came out around WWI, it was certainly available to Hitler and Goebbels, and I seem to remember sources claiming they were influenced by it. It projects a time of mass media in which governments will be able to control the discourse simply by establishing the term and context of it, producing so much print and images that alternative voices will only be able to get a word in in reference to that flood. Ronald Reagan once gave a twenty-minute speech that, on the program I was watching, was followed by an exasperated critic who threw up his hands at the daunting task of refuting all the lies told (I counted twenty, or one per minute). In the same amount of time available to him, this critic thoroughly refuted two to those lies, leaving eighteen that Reagan got away with!

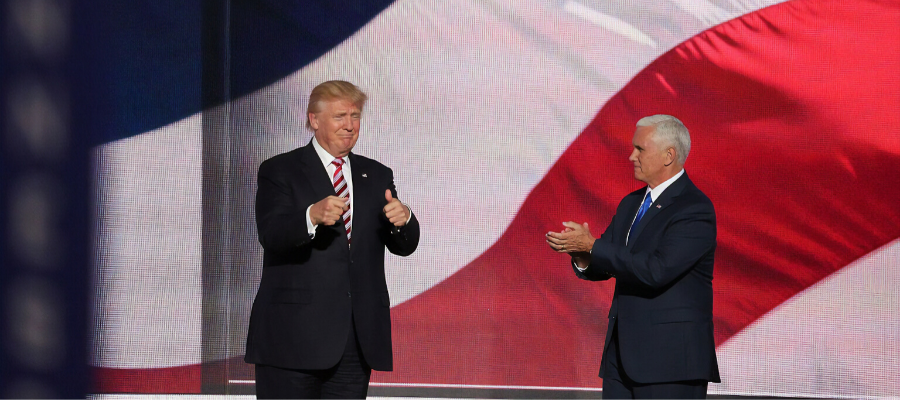

The picture above shows Trump with a full head of hair, even bangs that he can hardly keep out of his eyes. But the fact is, if he took the trouble to brush it back, we would see that it was not growing from the front of his scalp, as depicted, but combed forward from the nape of his neck, as so many vain older men do, and that he is quite bald. It's another case of the media phrasing events in available terms. That's all the propagandists need. In any case, his "popularity" is a myth, and has never exceeded about 7%, hardly a landslide in the making!

Another peccadillo that annoys the hell out of me is the way the Republicans get the media to go along with terms of its own making, there are many, but "Democrat" used as an adjective sets my teeth on edge. I suppose, to even the score, we should revise the term "Republican". Well, I will preserve the grammatical sense, but alter the ending that makes it an adjective, substituting a cognate for "can". And so, if it is proper to say "Democrat Party" it is also proper, and more telling, to say "Republic-ass Party".

Petercapra

Monday, January 4, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

It is not good news that evenIt is not good news that even the most titled teachers know so little psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud wrote, the first of the Future of an Illusion, Psychology of the Masses and Analysis of the Ego, where he explained in detail and live in the time of the advent of Nazism in his house (Austria), as does the Psychology Mass and especially what happens in the head of the individual - mass.

His best assistant Wilhelm Reich wrote the Mass Psychology and Fascism, and especially The Sexual Revolution, with which he explained in detail the mental weakness of the bourgeois middle and clung so easily because Fascist ideology. We must re-establish the education of the individual if want to make them immune from the danger of fascism, racism and hatred in general.

It 'impossible to achieve social responsibility without the responsibility of each individual.

A great responsibility we have as modern parents and teachers with children and students rather than to support consumption, fashions and the media that empty the brains

MJA

Tuesday, January 5, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

On Electing PresidentsOn Electing Presidents

I could never elect another to rule over or govern me, what about you? Who beside yourself would you trust? What about God, do you trust in God? How about God for president!!! And what about self-control? Why can't we all just elect ourselves to control ourselves, isn't that where our true power lies? Do we not give away our own self-determination, our own liberty, our freedom to others when we elect others to rule over or govern us. Is not self-determination self-control? Is that not what our the Declaration of Independence is all about? Is this surrendering of our freedom by electing others to rule us not a by-product of our state controlled education system? Did we not all have to start our school day, everyday with "I pledge allegiance to the flag". To a flag? "God bless America"? Well sprinkle some holy water on me, for surely I need to be saved. Until that day of salvation I can tell you this, the only person that I would ever go and vote for to govern me is myself. But I am not running for government, I run for health. Oh and if ever I were elected king or president or governor, the first thing I would do is disband the kingdom or the government and return the control to everyone equally. Just me,

=

KMcCMedia

Friday, January 8, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Interesting. As a BernieInteresting. As a Bernie supporter, I have to consider some of this, when contemplating my own enthusiasm for the political answer toward which I am gravitating....

Harold G. Neuman

Wednesday, January 27, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

A fascinating expose,A fascinating expose, Professor Smith.I have, over the last few years, developed some of my own notions regarding illusions and the like, and no, I am not at all confused or disbelieving of the Trump phenomenon. This season of political turmoil is most easily explained, on a fundamental level, as evolving out of the angst of an angry electorate. That is, of course, a simplistic and incomplete explanation, but fundamentals are expandable and I'll now attempt to do so. There is an idea out here (about which I have done some snooping around) which posits a relatively simple theory: with some notable exceptions that are beyond our control, some of which are due to chaos and other sorts of unpredictability, we get pretty much what we deserve. The originator of this set of conundrum-based predictions (a guy named Van Pelt) calls this the Historionic Effect. It explains, via numerous examples, just what Mr. Van Pelt is driving at.

Politics, and our preoccupation with it, seems to support the notion. Decade after decade and electoral process after electoral process we are sucked into the vortex of political frenzy, continually hoping that there will somehow be some final accomplishment; some eureka moment, during which as if by shamanistic hocus pocus, our system of governance will at last fulfill its lofty destiny. But, as you have so eloquently explained, it is all illusion and mere wishful thinking on the part of all of us. We continue to get just what we deserve, because we "buy the cow", believing she will deliver the milk we are yearning for. And, as a wise commentator once said some years ago, we get the best government money can buy. The gentleman from Vermont who is giving the Democratic front runner(?) fits is a strange, yet in some ways believable, voice of reason. No, his ideas would not work in a country of this size (socialized medicine works in those places where it does work because their populations are relatively much smaller than that of the United States).

But the very fact that he too is angry makes his message believable and, to some, attractive. We want to believe there is a better way to further our democracy and revitalize our political process.

Yes, the American people are frustrated and angry. They are looking for a better way out of the mess we are in and are anxious for a leader who can somehow make sense out of it all. Unfortunately, anger does little to solve a problem. And, inasmuch as revolution is unlikely, we shall probably blunder blindly forward as we have done for all the previously-referenced decades. Getting pretty much what we deserve.

Cordially,

Harold G. Neuman