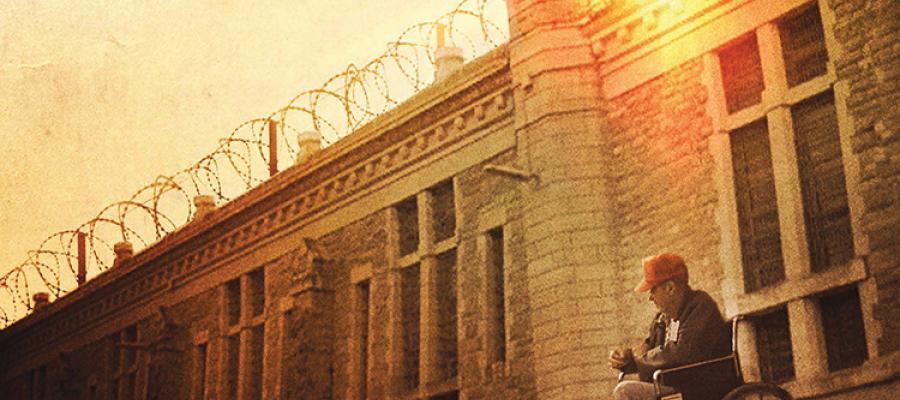

Dignity Denied: Life and Death in Prison

Jan 10, 2016According to the Treatment Advocacy Center, there are more people living with mental illness in prisons than in psychiatric hospitals across the country.

Because of some very harsh mandatory minimum sentencing laws, the U.S. incarcerates a huge number of people, many of whom are serving life without the possibility of parole. This country now has about one quarter of the world’s prison population, which is remarkable, if you consider that we’re not even 5% of the total world population. And our prison population is also rapidly aging, which means that it’s a population with more and more health issues. Of course, prisoners don’t exactly get the best healthcare in the world. So, many end up dying in terror, alone in their cells, from cancer, heart and lung disease, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses.

This strikes me as “cruel and unusual punishment,” which the Eighth Amendment prohibits. Well—it’s certainly cruel, albeit all too common in these times when politicians love to be seen as “tough on crime.” So, even if it’s not unusual, the most sensible interpretation of the Eighth Amendment is that it prohibits any punishment that is either cruel or unusual (Justice Antonin Scalia be damned!).

Of course, there is a philosophical question as to what kinds of actions ought to count as “cruel” and exactly how this prohibition is to be interpreted over time. Our own John Perry does an excellent job digging into this thorny issue and showing why Scalia’s interpretation of the Eighth Amendment is simply unreasonable and, moreover, incoherent.

Meanwhile, we need only consider how our view of certain punishments has changed over time. We no longer hang people in this country because that is deemed “cruel and unusual.” Ditto for the electric chair. Now, the raging debate is over whether certain drugs that are administered in death penalty cases constitute “cruel and unusual punishment.” I fail to see how there’s any controversy here. How could anyone sincerely believe that administering a drug that paralyzes an inmate while he dies a slow and painful death is anything other than cruel and unusual?

Clearly, I’m not a fan of the death penalty, in any form. So does that mean I ought to endorse life without the possibility of parole because at least it’s less cruel than the death penalty? No, this is just a false dilemma. There ought to be other options.

Consider a case. Imagine there is a young man in his twenties who commits a terrible crime and murders someone. He is tried and gets convicted to life in prison without parole. Now, forty years later, he has spent most of his life behind bars. Like any person forty years later, he is a completely different person than he was when he committed the crime in his youth. At some point during his sentence, he becomes seriously ill and is given just a few months left to live. What is the most humane thing to do here?

If it were up to me, I would simply release him to let him die in peace and dignity with his family. He’s already paid the price for his crime—anything else would just be cruel. In theory, inmates who find themselves in this situation can apply for compassionate release. However, because of the huge backlog of applications, in practice, many prisoners still end up dying alone in their cells before their cases are even processed.

To confound the problem further, just consider who is getting these harsh sentences in the first place. Many are non-violent drug offenders, who we know are disproportionately young men of color. Or they’re often mentally ill. Here’s a crazy fact for you—there are actually more mentally ill people in prisons in this country than there are in psychiatric facilities. Hospitals are being closed while more prisons are being built to incarcerate those already marginalized in society. And imagine what kind of care they get once inside. If they weren’t mentally unstable going in, they’ll probably be coming out. That is, if they don’t die inside first.

Our prison system is broken and needs to be completely overhauled. Denying someone their liberty is punishment enough. To deny them their human dignity, especially as they are dying, is simply cruel and unusual punishment.

Our guest this week is Edgar Barens, who made the 2013 Academy Award nominated documentary Prison Terminal: The Last Days of Private Jack Hall, which I highly recommend (bring tissues). He’ll be joining John and Ken to talk about how we can restore human dignity in the prison system.

Comments (16)

Or

Friday, January 8, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

When reading your post, itWhen reading your post, it strikes that we could bring to the table the Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution as well: "[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb . . . ." The clause prevents that a person be prosecuted twice for the same offense, and it also protects individuals from multiple punishment. It almost invites one to think that this clause could apply to cases like these as well in that one should not be punished twice for the same crime. But so often does the prisoner not only get punished with incarceration but also with not being allowed to seek or receive proper and dignified healthcare ? and that is a punishment, the effects of it varying depending on circumstance -, all for the same offense. It is not only cruelty but also double punishment. Denying access to reasonable healthcare is double punishment for the same offense and is in violation of a human right. So, I find, unless it is stipulated by the jury that x individual must be in prison for 20 years and that he shall not have access to reasonable healthcare, then access to adequate healthcare must be granted.

Gary M Washburn

Saturday, January 9, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

The idea of double jeopardyThe idea of double jeopardy is cute, but legally baseless. What the society does in response to a public disapprobration is not taken as the responsibility of the officers of the court. Like putting in stocks. Outlawry was the ancient equivalent, a condition in which any citizen could assault the outlaw with impunity, but the authority that declared that condition does not itself accept responsibility for the ultimate fate of those condemned to it, any more than it commands that assault. Robin Hood, after all, could have had the fate that the declaration of his outlawry might seem to entail. But it was with the Reformation that officials took upon themselves the power to impose penitential punishment upon the convicted. Previously, the punishment was meted out and that was that, but the imposition of penitence, replicating the imagined condition of "purgatory", emerged only as officialdom assumed the status of a divine corrective. There is still lingering a haughty sense of this moral requirement to bring the wrath of god upon the convicted, and the only relent to that wrath imagined by those who support such a view is the grace of that god somehow earned by the convicted, and any further ills that come to him or her after the sentence has been served is thought to be further proof of the rightness of that punishment and of that system of judicial retribution. But as that view ebbs, the view superseding it is vague and often has no terms to defeat its more archaic predecessor except pragmatism, which, after all, was, per Bentham, the handmaiden of what would become the "Panopticon", or "penitentiary". But the concept of justice that can appreciate the cruelty of excessive punishment, especially considering the slap-on-the-wrist response to upper class crimes, that are far more injurious to the public, that always accompanied the assumption of the role of justice as meting out divine judgment, brings into question the whole process of holding criminals responsible to the public for their offenses. Bereft the role of dispensing divine retribution, what right does the public have to punish anyone at all? As long as there is a disparity between lower and upper class enforcement of the law, this question looms as a pernicious vexation in law. But whatever rationale we assume for a pragmatic application of public indignation, if that view is the future of our penal code, it must limit itself to the effective application of that standard, and to bringing about that state of individual conduct implied. And where that state is achieved, there the responsibility to punish ends, and the public has thereafter a responsibility to see to it that punishment does end, even if this means prohibiting private individuals from holding an earlier infringement of law against the reformed individual. And this underscores an area of law, one of many, in which the public has a responsibility for taking actions that alter or mitigate private interests motives and actions. The thing is, that more enlightened view, and the older view of public righteousness, are profoundly seditious to each other, and we have not yet even found the terms to indict the older view, though it has long been equipped with the terms of its attack. It can be very dangerous to bring up an issue before we know all the implications the terms we are lacking in it, especially when the opponent has all its terms sharply drawn and well tested.

Slyphian

Saturday, January 9, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

You're weaving several issuesYou're weaving several issues and trying to weave one blanket out of them.

If you want to talk about reform in the criminal justice system then let's talk about that. Who we send to prison, for how long and for what crimes. I agree that this is an issue that needs to be talked about.

The rise in people with mental health issues in prisons is a direct result from liberals who felt it was cruel to put them in institutions where they were treated or managed. The closing of those institutions resulted in many of the previous patients being put out on the streets to fend for themselves, often without access to their medications. So they committed crimes to live, to get put in jail/prison so they had shelter and food and meds, or because they didn't know any better. Yes, there are better, and more cost effective ways of treating them, but learn from your previous actions. Simply kicking them out of prison to fend for themselves again won't work. Regardless of their mental state, they committed a crime, sometimes they should be treated, for other crimes there are no other options. The fact that they were off their meds won't bring back the person they killed.

One last quibble before I get to the main thrust of your post. Drop the "people of color" stuff. White is also a color.

I would like to see people supporting convicts rights care at least as much for the victims as they do the criminal. You maintain that dying, alone, in prison is cruel and unusual (which according to the Constitution BOTH criteria have to be met, not just one, it doesn't say cruel OR unusual) and we should consider how the criminal feels. He/she gave up many of their rights when they decided to deny other people, other citizens, their rights.

Where was the concern for Constitutional rights when this person kidnapped a child, tortured and raped him/her repeated over the course of weeks, before they killed him/her. With the victim alone, away from family or loved ones, with no dignity. Isn't that also cruel and unusual, more so because this victim did nothing wrong?

Isn't as cruel and unusual to make the victims pay to support the criminal who violated their rights, for any amount of time? It's very little different than a judge telling the victims that they have to take the criminal into their house, feed, clothe and shelter him/her for a given amount of time. Prison is just a way of doing it by proxy. It's not the criminal who's paying, it's the victims who are still paying.

Yes, let's take your case of the 20 something year old who MURDERED someone 40 years previously. He's now 60 something. No career, no job, no way to support himself. Chances are his parents are gone, his siblings,if he has any, may or may not want anything to do with him, much less support him. He may or may not have any children, and if he does, will they want anything to do with him? They probably don't know him very well, if at all, they probably have lives of their own children of their own and may not want Dad/Grandpa around their kids. He has no Social Security or any other means to support himself.

So, let's be "humane" and kick him out of prison, probably into the streets, or maybe, at best, a halfway house or some such, onto the welfare system, where he'll probably still die alone and without treatment, so you can feel good that you "saved" someone.

You, in your Rockwellian view of life, naturally assume that his family is still around (if he really had one) and wants anything to do with him and take him in. You, of course argue that he's not the same person he was 40 years ago, at least he HAD 40 years to, possibly, change. Unlike his victim.

To say that prison is a punishment for crime is akin to saying that taxes are a punishment for working. It's more a natural consequence for choices made. I, as a citizen, have the human right to walk and live in my community without fear of someone stealing what I worked for, without fear of being assaulted or murdered. These are societies norms, if there are no consequences to those who violate those norms what is the point of having them?

Yes, the consequences should be proportional to the crimes, for everyone. Rich or poor, white or black, male or female. Politically connected or not.

The prison system is not broken. The justice system is flawed. I can't call it the criminal justice system because there is no need for justice for a criminal, the victims and society need justice, not the criminal. It needs improvement, or better yet we need to fix the things that lead many people into crime and into the justice system. Work to keep them out of the system in the first place.

The importance of families, 2 parents, same sex or not, for all kids, regardless of race or income status. Improved educational opportunities, in both inner cities and rural communities. Poor education is not just an inner city issue. Many rural, farming, and predominately white communities, have equally as poor educational systems as inner cities. They just don't use it as an excuse and crutch for poor choices.

Income inequality, which can lead to increased crime and substance abuse. If you have little money and little hope you do what you can to survive or to numb yourself to your situation.

While there are many factors that lead, even encourage, a person to commit a crime, ultimately they made a CHOICE to commit the crime. Far more people live in the same conditions as others and never commit a crime. While we need to work on contributing factors that lead to crime we also need to work on why individuals make the choice to commit crimes and having a deterrent as an incentive to make the societally correct choices is one such factor.

Gary M Washburn

Saturday, January 9, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Are there no prisons? AreAre there no prisons? Are there no workhouses workhouses?....,

The most violent crimes committed are plotted in boardrooms, not in the streets. The movement of the mentally ill into prisons did happen quite as stated. Have you ever seen the movie Titticutt Follies? The madhouses of the era were a disgrace, which were ordered shut on medical, as well as humanitarian grounds. It was decided that the local communities bore responsibility for the treatment of their mentally ill as well as for the education of the learning impaired. But the local communities either failed to step up to the job, or were thwarted by vocal NYMBY groups, and the expansion of education to include the learning impaired proved so expensive it handed a powerful weapon to the "small government" movement, not to mention desegregation, which broke up the New Deal coalition once and for all. The notorious fallacy of characterizing justice by the extreme case is a rhetorical device, not responsible argumentation. Because a few criminals are incorrigible does not make it just to impose excessive punishments on the rest. In law, punishment is on behalf of society as a whole, not retribution in the name of the victim. Lex talionus is not a mandate that justice requires a punishment equal to the crime, if it did, then why do some get many years in jail for a few hundred dollars theft? No, that maxim must be taken, not as a requirement to match the harm done, but as a maximum beyond which justice cannot go. In which case most now in jail have no business being kept there. A more typical case is the guy caught with a few joints in jail for a decade or more, or the sap who couldn't get to the court to pay the parking fine and ends up jailed for months, based primarily on court assigned fees that he is too poor to make good. If you want to do justice, it's a good deal more responsible to take into consideration who is actually being punished, and why. Minimum sentences are a throwback to the days when pickpockets were hung for stealing a silk hanky, or poachers for snaring a hare.

Or

Saturday, January 9, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

The current system of removalThe current system of removal of healthcare rights doesn?t help the victims or the perpetrators. If we?ve gotten to the point where to deal with crime is to take away basic rights, then something is seriously wrong. Where is the morality in patronizing double punishment? The aim should be to prevent these crimes from happening again. But insensible incarceration and removal of healthcare rights only leads to further damage, not only for the perpetrator of the crime but for, say, the family of the victim, who must now, without a say in the matter, carry the burden of being tied to a system that they might find unjust.

And not in all cases are the perpetrators of crime able to sidestep the circumstances that lead them to crime in the first place. Take medically-tainted cases: a person who kills an innocent (who happened to be in the way) due to a schizophrenia crisis is a murderer but also a victim of his illness. An alcoholic who kills a kid crossing the street is a culprit but also a victim of his/her alcoholism disease, and so on. Granted, these are specific cases, and I am not in any way justifying the actions committed. But are these people really aware that they are giving up their rights and taking away the rights of others and thus should have all their rights removed once incarcerated? In view of this, how can we morally and ethically continue to sustain that the punishment system that we actually have in place is helping anybody? Does it really help the victims (both the person done harm against, their family, and the perpetrator)? Aren?t we actually putting on the victim and their family the responsibility of carrying on their shoulders a punishment system that is amoral (if they believe it is so)? As a society we should work to prevent crime from happening in first place, of course while justly punishing the perpetrator (which is done via his or her incarceration, nothing more), and if not that then at least that a criminal does not repeat offenses.

Gary M Washburn

Sunday, January 10, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Crime is not limited toCrime is not limited to violence. Some crimes are the social effects of individuals taking actions that seem perfectly reasonable to them. The effect of excessive incarceration and subsequent denial of rights is to suppress the political and economic rights, not only of individuals, but of the political class to which they belong. And if the state has any responsibility at all (and states have no rights, but only powers incumbent upon the pursuit of its responsibilities) it is to mitigate the socially pernicious effects of individual action. Actions like creating slums by moving into a "good neighborhood", creating inferior schools by moving to richer school districts, creating an underclass by applying prejudicial standards in reviewing applicants, or in voting for an excessively punitive penal system. There is no case in law that is not individual, but law is always written as if justice were in principle a generality. There is no moral generality. Morality is this moment, not an abstract of others to which this case is somehow made to fit. What is right to do in this case can only be prejudiced by another. But such is the perversity of the human mind that it always tries to generalize what is in every case unique. But can we create a state which mitigates this? Not if we base it upon a process of choosing sides. Because the pernicious result of judging the unique in generalized terms is the emergence of such sides or factions. The possibility of the just state rests upon mitigating the zero-sum game that emerges as the pattern of individual actions coalescing into divisions that perpetrate social crimes just as vital for the state to address as individual violence.

John Perry

Tuesday, January 12, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

In regards to Slyphian,

Consider,

(1) Cruel and unusual punishments shall not be inflicted.

Does this mean that only punishments that are both cruel and unusual are ruled out, or that punishments that are cruel are ruled out, and so are punishments that are unusual? Compare

(2) Pork and beef products are not eaten by vegetarians.

The natural reading is

(3) Pork products are not eaten by vegetarians and meat products are not eaten by vegetarians.

It might be possible to take (2) to only rule out things like stews with both beef and pork, but it?s not a natural reading.

Adjectives and nouns have connotations and denotations. The connotation is the property a thing has to have for the term to apply. The denotation is the set of things that have the property. The word ?and? can serve to combine the connotations, giving a complex property, such as

being a punishment that is both cruel and unusual

being a product that is both beef and pork

In this case the denotation is the intersection of the denotations of ?product?, ?beef? and ?pork?, or of ?punishment?, ?cruel? and ?unusual?. Call this the ?intersection? reading.

But 'and' can also be used, and more commonly is used, to combine the denotations. Take the denotations of ?product? and ?pork? and ?beef? and combine them, giving us the union. Call this the union interpretation.

Observations

(i) When the intersection is empty, the intersection reading is usually hard to get. If we say

(4) Expensive and cheap restaurants should not be considered

we clearly mean to rule out both expensive restaurants and cheap restaurants, not simply restaurants that are both cheap and expensive.

(ii) When the intersection reading is intended, in English, usually a comma or nothing is used rather than ?and?:

(5) Late disorganized papers will not be graded

(6) Late, disorganized papers will not be graded

both seem to allow papers that are disorganized but handed in on time, and papers that are late but well-organized. Whereas

(7) Late and disorganized papers will not be graded

is much more likely to be read as excluding the late organized papers and the on-time disorganized papers.

So, going back to

(1) Cruel and unusual punishments shall not be inflicted,

it seems that the union reading is both possible, and preferred, pace Scalia and Slyphian

Gary M Washburn

Wednesday, January 13, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Laying down the law? WhatLaying down the law? What force does it have? Does double jeopardy apply? Is it cruel and unusual to pull out formal analysis? Problem is, its force relies on consent. The mind is not slave to its form. It must be free to win every term of that form, and, more obviously, every term within it. For those terms do not follow the form. And it is a rigor of objection, as much to form as to claims of "connotation" or "construal", that drives the process by which we suppose there are rigid formal laws. Some call it a play, but if it is a game it is one that is far more serious than "games theory". It is a recognition that we have no unilateral right to be understood. That is the fundamental law of mind. We need each other free.

But what about the criminal code? The conservative view is that an orderly society requires coercive force to prevent violation of person and property. But this is at best a simplification prejudicial on behalf of those who have more to defend or to gain from it. And civil law is infamous for leniency to social violence that enlists its support. Those who most influence the law are most inclined to suppose a social requirement that it defend them, even as they engage in the greatest scale of criminal activity. The real question is, what is the meaning of the law in the first place? The fact is, orderly behavior is not only normal and occurring without lawful force at all, but that most of our institutions take that innate orderliness of human behavior for granted, and even use it to bilk unsuspecting citizens of their rights. rights that should be incumbent upon the orderliness of their behavior. But is the law in service to that innate orderliness, or to those who use it as the means to commit, highly orderly, crimes against us? The ancient suppositions of why law should be obeyed at all have eroded to a point that they can only sustain themselves with an increasingly shrill fanaticism, while that frenzied clinging to the past inhibits the real question. By what right does the law impose itself upon us? What is the law really doing? Revenge is not justice. "An eye for an eye blinds the world", as Gandhi said. Justice is not for the victim, nor for the restoration of some mystical or divine balance. But what is it for? But until we have an answer, pragmatism will have to do. And pragmatism is anathema to extremes. But if the force of logic is an expression of our needing each other free, in what sense is law?

John Perry

Wednesday, January 13, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

This is a revision of myThis is a revision of my earlier post, with a new example and corrected analysis.

Re; Slyphian

Consider,

(1) Cruel and unusual punishments shall not be inflicted.

Does this mean that punishments that only punishments that are both cruel and unusual are ruled out, or that punishments that are cruel are rules out, and so are punishments that are cruel?

Compare

(2) Pork and beef products are not eaten by vegetarians.

The natural reading is

(3) Pork products are not eaten by vegetarians and meat products are not eaten by vegetarians.

It might be possible to take (2) to only rule out things like stews with both beef and pork, but it?s not a natural reading.

Another example, from Devon:

(D) The Boys and Girls Clubs of America are not co-ed.

One might read this as a contradiction. But it is more plausible to read it as

(D?) The Boys Clubs of America are not co-ed and the Girls Clubs of America are not co-ed.

Adjectives and nouns have connotations and denotations. The connotation is the property a thing has to have for the term to apply. The denotation is the set of things that have the property. The word ?and? can serve to combine the connotations, giving a complex property, such as

Being a punishment that is both cruel and unusual

Being a product that is both beef and pork

In this case the denotation is the intersection of the denotations of ?product?, ?beef? and ?pork?, or of ?punishment?, ?cruel? and ?unusual?. Call this the ?intersection? reading.

But it can also be used, and more commonly is used, to combine the denotations. Take the denotations of ?pork? and ?beef? and combine them, giving us the union. Then take the intersection of this set and the denotation of ?product?. We get the set of products that are pork and products that are beef. Call this the union interpretation.

Observations (i)

When the intersection is empty, the intersection reading is usually hard to get. If we say

(4) Expensive and cheap restaurants should not be considered

we clearly mean to rule out both expensive restaurants and cheap restaurants, not simply restaurants that are both cheap and expensive.

Observation (ii)

When the intersection reading is intended, in English, usually a comma or nothing is used rather than ?and?:

(5) Late disorganized papers will not be graded

(6) Late, disorganized papers will not be graded

both seem to allow papers that are disorganized but handed in on time, and papers that are late but well-organized. Whereas

(7) Late and disorganized papers will not be graded

is much more likely to be read as excluding the late organized papers and the on-time disorganized papers.

So, going back to

(1) Cruel and unusual punishments shall not be inflicted,

it seems that the union reading is both possible, and preferred, pace Scalia and Sylphian.

Gary M Washburn

Thursday, January 14, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

But what does "union" mean?But what does "union" mean? What does "is" (or "will be")? Are the terms of the "union" same or different? What logic either? Is the reduction of a "conjunction" subjunctive? The law of contradiction does not apply as you imply it, for it is not there a formal a priori. If there are any troubling questions about any of this, what the hell gives you the right to threaten a bad grade? As for Scalia, I wish him no peace at all. His peace of mind is a plague upon us.

Gary M Washburn

Friday, January 15, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Shades of Willie Horton.Shades of Willie Horton. Prevention? Since when is it the job of the judicial system to prevent crime? Sounds like reading tea leaves to me. Punishing people for potential crime is an institutional crime worse than any individual is ever going to commit. The fact is, as cases like Newtown show us, if we suppose we can predict what people are likely to do many thousands will be punished for crimes they probably never would have committed. There is no "criminally inclined" characteristic that does not show up in many law-abiding people. The punishment must fit the crime, period. It is no more the job of the judicial system to predict future behavior of convicted criminals than of those who never committed any crime. We do indeed review cases as to whether they deserve parole or early release, and in most cases they get it right, though more resources wouldn't go amiss. Another fact is that most of the people in our prisons never committed an act of violence and probably never will. So the whole issue of a responsibility to prevent crime is simply misapplied to the prosecution of the law. Enforcement, yes, but that is much less a matter of "getting bad guys" than it is of creating a social atmosphere in which people are disinclined to break the law in any socially toxic way. Good policing is far better than numerous arrests. It's a matter of making everyone feel they are on the same side of the law. Harsh sentencing is lethal to that goal.

Harold G. Neuman

Wednesday, January 20, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

If having a system of lawsIf having a system of laws does little or nothing towards prevention of crime (as Mr. Washburn suggests), then why do we have such a system in the first place? Well, I think most of us are at least marginally comforted by the fact that we do have a system of laws, otherwise we may as well return to the chaos of total lawlessness. Personally, I have grappled with the problem of life sentencing for several decades and still cannot grasp any sort of solution. Probably because there is none-greater minds than mine would have surely implemented such by now, don't you think? But regardless of what we may choose to think of law and jurisprudence, conventional wisdom (i.e., criminology) seems to uphold the notion of punishment as deterrent. And, in a nod to Laura's dilemma, it also appears that some violent criminals do experience rehabilitation, managing to exit the halls of punishment and discover productive lives.

One (if not the primary) aim of Christianity was to keep believers in line. The whole idea of the Commandments was to gently encourage believers to treat each other with respect, love and human kindness and to not kill, maim, cheat, covet, lie to, or otherwise make each other's lives miserable. However, as we are predisposed to do, humanity evolved, questioning ever more often the wisdom of teachings and the efficacy of holding to them. And, it seems rather certain that a similar evolution has been proceeding in other belief systems, so that, in order to regain order, law and jurisprudence have, in like manner, evolved. So, we apprehend, indict, try, and imprison criminals, and, in severe cases, we feel compelled to end their lives. And we decry,discuss and debate the effectiveness of cruel and unusual punishment. Clearly, we must do something to uphold the common good. Clearly (whether we like it or not), our system(s) has/have some deterrent effect-otherwise, there would be a lot more murders and murderers than there are already. I stated before that I thought forgiveness should have an expiration date. I still think so. It is true, too, that some folks deserve second chances. But if we were to summarily grant second chances to murderers, that would surely negate punishment as a deterrent. Immediately, if not sooner: even more murderers and their victims (uh, I hope we can agree that murdered people ARE victims?) All right. I have taken enough time on this. The problem is not going away any time soon. It is, in that sense, a lot like politics, is it not?

Cordially,

Neuman.

Gary M Washburn

Wednesday, January 20, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

The Nazarene, if you take aThe Nazarene, if you take a close and yet expansive look at his life and times, was clearly trying to find a way for the Jews to become reconciled to Roman rule. That's all. He failed. He did not author the "commandments", Moses did, and most of the hundreds of them are rather silly, but we ignore these (like, "boileth not the meat of the calf in the milk of its mother"). But it is easy to forget how cruel this code of law is, and how cruelly it was enforced (by the community crime of stoning).The fact is, the law does not make us law-abiding, it is an expression of our being law-abiding, and provides a sort of rule-book in a society become too complex for intuition to suffice. There are indeed some few who will violate that sociability in us, but far the worst crimes are ones that involve the supposition that some are not within the law and therefore need the law to order their lives. And when those convinced of that supposition write the laws the law itself becomes the criminal. But what distresses me most about this fallacy of "law-and-order" is that its premiss tacilty relies upon the very law-abiding nature of humanity in its much too vehemently explicit repudiation of it. The result is sanctimony, and the kind of unjust laws that put us on the road to a society divided between saints and sinners, and thereby masters and slaves. And where a stated motive is fallacy, I feel justified in reading into it a motive evidenced by the effect. Which is to say, a legal system that is criminal in effect is criminal by intent.

Gary M Washburn

Thursday, January 21, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Hammurabi was a dear,Hammurabi was a dear,

Hammurabi had no fear,

But Hammurabi had no rabbi

Had he?

Harold G. Neuman

Sunday, January 24, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

Wherever you go, whatever youWherever you go, whatever you do;

There are always a few, who will aggravate you.

The obverse, of course, as the cart with the horse:

A ubiquitous few, are disgruntled by you.

Cheers,

Neuman.

Gary M Washburn

Sunday, January 24, 2016 -- 4:00 PM

The code of Hammurabi isThe code of Hammurabi is often hailed as liberating the law from arbitrary rule, but it was quite arbitrary and meant to enslave. The 'law of Moses', actually comprising hundreds of clauses, was confabulated by expatriates kicked out of their cushy lives in Babylon after the Persian conquest who made the best of it by compiling a scriptural account with which to dominate the people of Israel, where they were forced to return. That is, like the code of Hammurabi, the Bible is meant to enslave. The spirit of the law is not to be found in writing. The partisans to the written do tend to get disgruntled by the unruly reality of the spoken word.