Does Science Over-reach?

Jul 22, 2018We've all heard the phrase, "You can't argue with science." Appealing to scientific fact as a way to settle a question makes sense give...

Ever since the replication crisis broke in around 2011, a number of causes—more and less nefarious—have been identified for why a psychological experiment (or other experiments) might not replicate.

For those who missed it, the replication crisis was the discovery in psychology that many of the field’s apparently significant results didn’t replicate. That is, when independent researchers did the same experiments as ones already published, the previously found results didn’t materialize. The replication crisis gained momentum largely due to a replication effort spearheaded by Brian Nosek of University of Virginia. He and 270 other researchers re-did 100 of the most famous results published in 2008. They found only 30-40% of those re-done experiments replicated the original results (depending on which statistical tests one applies to the data).

When it comes to the root causes of the crisis, the most important problem (out of several) seems to have been a bias on the part of journals for publishing eye-popping results, combined with a too-lenient standard of statistical significance. In the past, experimental data only had to pass the significance test of p < 0.05 in order to be publishable. An experiment whose data achieve that level of significance has a 5% chance (or less) of having gotten its apparent effect by accident. That might seem good. But think of accidentally passing that test for statistical significance as rolling a 19 on a 20-sided die; even if your experiment isn’t meaningful, you might have gotten lucky and rolled a 19. So with many thousands of studies being done each year, the consequence was that hundreds of studies hit that level of significance by chance. And many of those hundreds of studies also had eye-popping “results,” so they got published. There are several easy-to-follow overviews of the replication crisis available (e.g., here and here), so I won’t expand on the general situation.

Rather, I want to go into a different possible reason why a study might fail to replicate, one that seems to have been mostly overlooked, namely: lack of conceptual clarity about the phenomenon being measured. This could be lack of clarity in the instructions given to participants or even in the background thinking of the experimenters themselves.

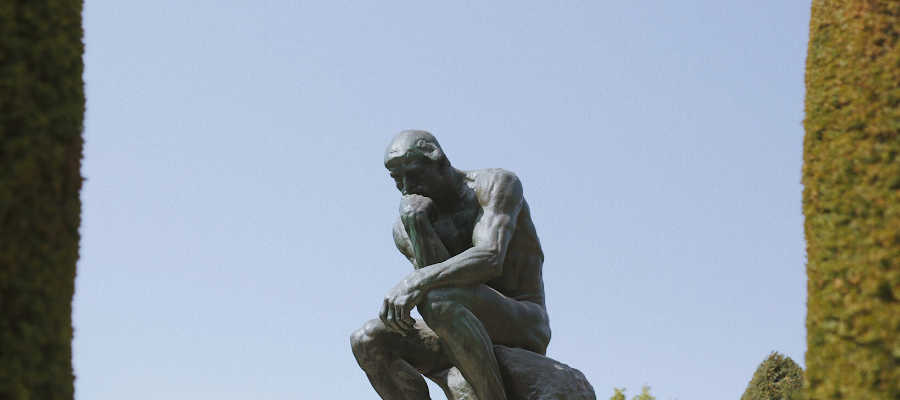

One of the more famous studies that didn’t replicate was published in Science in 2012. Will Gervais and Ara Norenzayan did five experiments that seemed to show that priming participants to think in analytic ways lowered their levels of religious belief. For example, getting participants to do word problems in which analytic thinking was needed to override intuitions apparently lowered their level of belief in supernatural agents, like ghosts and spirits. Gervais and Norenzayan even found that showing participants images of Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker (pictured above) lowered measured levels of religious belief. The topic of such studies is exciting enough to get published in a top journal: if this were a real phenomenon, then just getting people to think a bit harder would start to undermine their religious beliefs.

Too bad attempts to replicate Gervais and Norenzayan’s findings came up empty handed. Now, to be fair, there is a real phenomenon in the ballpark that has turned up in various studies: people who have a more analytic cognitive style in general—meaning they’re prone to using logically explicit reasoning to overrule intuitions—are less religious. But that’s a finding about a general personality trait, not the effect of in-the-moment priming.

Applying my suggestion to Gervais and Norenzayan’s studies we can ask the following: how might lack of conceptual clarity on the part of participants help engender a situation that’s ripe for replication failure? There are two things to say. First, lack of conceptual clarity may lead to a situation in which there is no determinate phenomenon that’s being probed. If that’s the case, then a given experiment, though it might seem to be about a determinate topic, is really just another roll of the 20-sided die. But that roll might come up 19, so to speak, in which case it could well get published. But second—and more subtly—in the presence of conceptual unclarity on the part of participants, irrelevant influences (like idiosyncrasies of a particular experimental location) have a better chance to sway participants’ answers, since they don’t have a clear grasp on what’s being asked. Irrelevant influences mean that factors about a particular experimental situation prompt participants to answer one way rather than another, even though those factors have nothing to do with the topic being researched. If that happens, then when the study is replicated in a situation where those irrelevant influences are absent, the apparent effect is likely to disappear.

Take Gervais and Norenzayan’s Study 2, for example—the one in which participants looked at an image of Rodin’s Thinker and then reported on their level of religious belief. Gervais and Norenzayan found that their participants who saw an image of The Thinker reported lower levels of religious belief than their participants who saw images not associated with analytic thinking. But what was their measure of level of religious belief? They write, “a sample of Canadian undergraduates rated their belief in God (from 0 to 100) after being randomly assigned to view four images…of either artwork depicting a reflective thinking pose…or control artwork matched for surface characteristics…” [my italics].

Now ask yourself: what does a 56 point as opposed to a 67 point rating of belief in God (out of 100) even mean? There are various things that might come to mind when such a rating is requested. One might take oneself to be rating how confident one feels that God exists; that means giving an epistemic rating to the belief. Or one might take oneself to be rating how central “believing” in God is to one’s identity; this means giving a social rating to the belief. And these two things come apart. Many devout Christians, for example, admit in private that they wrestle with doubts about God’s existence (low epistemic confidence), even as they dutifully attend church every week (high degree of social identity). And without clarity about what their answers even mean, participants might well be pushed and pulled by irrelevant contextual factors that create some sort of response bias (the placement of response buttons on their keyboards, or whatever).

It is, I confess, only a guess to say that lack of conceptual clarity on the part of the participants was implicated in the not-to-be-replicated data in Gervais and Norenzayan’s original study. Furthermore, measures can often be meaningful even when—or sometimes especially when—participants have no idea what’s being measured. But it’s fair to say that in at least some cases, lack of clarity on the part of participants about what’s being asked of them can lead to confusion, and this confusion opens the door for irrelevant influences.

The good news about the unfolding of this crisis so far is that many researchers in psychology got their acts together in three key ways. First, researchers now use more stringent statistical tests for whether their results are worth publishing. Second, pre-registering studies has become standard. Pre-registration means that researchers doing an experiment write-down in advance what their methods and analyses will be and submit that document to a third-party database. Pre-registration is useful because it helps prevent p-hacking and data-peeking. And third, it’s become more common to attempt to replicate findings before submitting results to a scientific journal. That means that a given experiment (or one with variations) gets done more than once, and the results need to show up in each iteration. Thus, researchers are checking themselves to make sure they didn’t get single-experiment data that just happen to pass tests for statistical significance by accident.

The moral of the present discussion is that there’s an additional area of room for improvement. Sometimes a philosophical question needs to be asked in the process of experimental design. If you’re an experimenter who wants to ask participants to give responses of type X, you would do well to ask yourself, “What does a response of type X even mean?” If you’re not clear about this, your participants probably won’t be either.

Comments (1)

Harold G. Neuman

Wednesday, January 23, 2019 -- 2:12 PM

Undoubtedly, there is goodUndoubtedly, there is good reason for replicability of results in most any science-based research---that point is well made in your post and has been so elsewhere for a very long time. I guess this shows, as mentioned before, cross-disciplinary relationships among philosophy; psychology; psychoanalysis; physiology; and neuroscience. I know comparatively little about philosophy and comparatively even less about psychology, but, to me at least, Philosophy Talk is primarily about philosophy---which is why I enjoy it and the lively participation it encourages. If the primary purpose of the blog is furtherance of philosophical thought and discourse, then let's get on with that. If psychology merits a blog of its own, why not establish one? Call me a purist or a cretin, if you like, but I would not have been particularly interested in this blog, had it been called Psychology Talk. Just sayin'...