What if gravity suddenly stopped working? Or what if e gradually came to equal mc3 rather than mc2? Could the fundamentals of physics really change? Or Is this just the stuff of science fiction? That’s the question we’re addressing this week on Philosophy Talk.

Now I must admit that part of me wonders whether this idea even makes sense. I admit, though, that we can surely imagine such a thing. Early in the history of the cosmos, the fundamental constants have one set of values. Later, they have a different set. No doubt that would be surprising, but the idea itself isn’t incoherent, I suppose—which is what saying it doesn’t make any sense would seem to imply.

But surprising also doesn’t do it justice. The Cubs winning the World Series—that was surprising. The strength of gravity changing? That would be more than merely surprising. I’m not exactly sure what the right word is. Mystifying, perhaps? Whatever word you want to use, it would need some explaining.

But that’s precisely the problem. It is hard to imagine what the explanation could possibly be. We can’t appeal to even more fundamental laws to do the explaining. That would mean that the original laws weren’t fundamental after all. The only other possibility that I can see off the top of my head is that the fundamental laws could somehow explain their own evolution. But that seems… paradoxical.

But perhaps we’re thinking of it the wrong way. So far, we suppose that the universe is this very big and ever evolving totality. We also assume that the evolution of the universe simply must be governed by a ground floor of fixed unchangeable laws that hold everywhere and every-when. It’s a lovely and elegant picture. And it’s one that we inherited from the incomparable Newton. Moreover, it’s worked awfully well, at least up until now. And though I’m not really suggesting we should abandon this Newtonian picture, it has left us with questions that we can’t answer. For example, it can’t really hope to explain why we have just the laws we have, rather than some other laws. Indeed, the Newtonian picture assumes that the basic laws themselves need not explanation—at least no explanation from within physics. From the point of view of physics, the fundamental laws just are. That’s just part of what it means for laws to be fundamental.

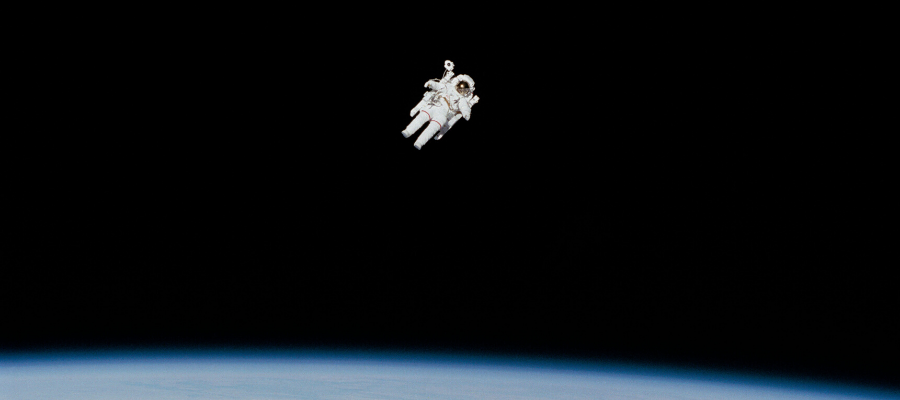

But the laws governing our universe aren’t just any old laws. They’re really very special laws. To appreciate just how special just look around you! The laws have produced an amazingly complex and delightful universe. It’s like it was designed by an architect with an incredibly rich imagination. Now I’m not suggesting that we should accept intelligent design. But the advocates of that approach are addressing a real, so far unanswered question. And it's not just that it hasn’t been answered yet. It may well be in principle unanswerable within our broadly Newtonian framework.

To fully appreciate how special our laws are, you allow yourself to be amazed by the mere fact of our universe. There are many, many ways that our universe might have turned out. And it wouldn’t have taken very much at all for it to be completely different than it is. If the masses of the different elementary particles, or the strengths of the fundamental forces had differed ever so slightly, the universe would be more like a puddle than like a vast and varied menagerie. Now it’s a darned good thing that we don’t live in a puddle-verse. The million dollar question is WHY we don’t. Of all the universes that there could have been, how and why did it happen that the universe turned out just the way and it did and not some other of the myriad of ways it might have turned out. Why are the laws, constants and parameters tuned just enough to avoid a puddle-verse and to yield a menagerie instead?

Some are tempted to say even here that there is no explanation needed. But that reduces the universe to something like a lucky accident. Another, increasingly popular explanation is the idea of a multiverse. And that may be a start of insight. But if every possible universe is simultaneously actual, then NONE of them is special in the right way.

But what if the multiverse is sequential rather than simultaneous? Suppose, that is, that the laws, the parameters, and the constants literally evolve over time. Think of a self-organizing universe trying out, over time, various alternative configurations. Over time, through a process of cosmic selection, a universe with just the right laws, just the right parameters and constants, and just the right values gradually emerges.

The analogy to biological evolution should be obvious. Instead of biology, though, we’re taking cosmology—evolutionary cosmology. Evolutionary cosmology involves cosmic selection instead of natural selection. Cosmic selection gradually designs the universe the way natural selection gradually designs the bioverse. It preserves interesting universes and discards puddle-verses. And we have something like survival of the fittest universe. Now the beauty of this idea is that without appealing to an outside designer, it answers the question—“Why just these laws, rather than some others?” Answer: “A universe governed by them is more cosmically fit!”

The physicist Lee Smolin has proposed a rather more sophisticated theory of something like the approach just outlines. And I gather many take the idea seriously, as a hypothesis worth thinking about, even if they don’t quite endorse it. I myself can’t quite get my head around even the spirit of his approach—let alone the details, which are way beyond my depth. My problem is that it seems like cosmic selection would itself have to be governed by… well… laws. And wouldn’t those laws be the truly fundamental ones? And it just doesn’t seem likely that the a law governed process could explain the evolution of the laws that do the governing. In the end, I guess I’m just stuck on Newton, aren’t you? That’s not surprising. He’s hard to get over.

Still, it should be an interesting discussion—a truly mind-bending one. We’ve got a great guest and a great guest host—both of whom know a lot a more about this topic than I do. Maybe they can help me get my head around the idea that the fundamental laws of physics might possibly be the sorts of things that change and evolve.

Comments (2)

Tim Smith

Wednesday, December 11, 2019 -- 6:42 AM

Physics has so so much to do.Physics has so so much to do.

Newton was falsely taken in by his times and internecine academic rivalry to rise above his inherent bias toward the fundamentality of creation. He saw it as part and parcel of his world view. I would have to read his work much more in depth to say whether the previous sentence is right or not. Now that I have said it... I think back and I do recall several passages where Newton seems to break and speak directly to the reader, like Galen, that the reader or future generations must decide and look.

Regardless of Newton's own view, his very astute insight has caused us all to believe we understand the heavens and that laws here are laws there... and by this profundity... laws exist. They don't. Einstein has done worse. He has defied reason, used his own profundity to question entanglement... and by this denial... created a bit of a cult. Science persists with or without cults but is the worse for indulging them. This evidenced in wasted effort and denial of plausible alternative hypotheses. It is a sham that Darpa is often the forward thinking fund source over our own public science. But ... I digress.

Causality is fine to presume. I prefer turtles all the way down. Physics has it's own emergent paradigms that defy causal reasoning... I think.

Why are there 12 fermions and only 3 required to make everything we know? What do the other nine do? What is dark matter or dark energy and why can't we detect it like Newton detected gravity? Why is dark matter only interactive gravitationally on cosmic scales? Why is gravity so weak and why no graviton? Why can we only touch 5% of matter? The list goes on and on... Physics is a mess. Don't get me started on funding. There is a phoneme that leads to a Lewis Carrollian rabbit hole. Again I digress... but it is all about the benjamins.

Yet Physics is pointed to as a fundamental science. It is not. It is only a science. A very important science but not the most important one. Certainly it is no indicator of immutable laws, which is what Newton unfortunately promulgated.

I have a very difficult time seeing how we could detect laws changing on cosmic or even personal scales when time and perception are tied to activity and proximity in the brain. Remove the fusiform gyrus and we can't recognize faces yet we still understand the concept of face and even see it?? I'm not sure generational perceptions are preserved in my own lifetime. The laws of physics could alter over millenia and this just may not compute. We haven't done that either much less explained the super voids of the cosmos.

Particles hit the earth, millions of them, at velocities that defy explanation. There are laws to be re-written. Bring on the turtles. Science is all about the turtles ... all the way down.

This is kind of cool. You can download an app to help detect these cosmic rays... https://crayfis.io/about

I don't know what made me add on that last plug... I'm not sure there is causality. But I too am not betting my pension on that.

I will cross post this with the 2019 show... I'm a bit incapacitated at the moment and wandering about books and the web ... though PT is best taken with headphones and yard work.. it's fun to read the comments and get into a blog post or two.

https://www.philosophytalk.org/shows/could-laws-physics-ever-change

stevegoldfield

Sunday, December 22, 2019 -- 12:13 PM

Your basic question is muddy,Your basic question is muddy, and that skews the discussion. What do you mean by "the laws of physics"? Do you mean the equations of physics, physical constants, or their combination, for instance. There are important physical constants, for example, which make life and our universe's structure possible. If they were even very slightly different things would fall apart, even though the equations of physics might not change. I heard the question, what if e = mc squared changed to e = mc cubed? First of all, Einstein derived that equation from other parameters, and it is incomplete. Mass times the speed of light squared is only the first term. The other terms are generally ignored because they are much, much smaller. The speed of light (in a vacuum) is one of those physical constants. It could be slightly different, and the equations might not change, but physical reality could be very different. Water has unusual properties which make life possible: its maximum density is at 39F, which is why streams don't freeze from the bottom up and kill all the fish. It has many other life-permitting properties, such as its heat capacity, its buffering capacity, and its colligative properties. So, there are so many things in nature which could be different aside from the underlying equations. Some cosmologists speculate that if there is a multiverse, basic constants, such as Planck's constant, could have different values. That could mean that we just happen to live in a universe in which our form of life is possible so our view is inevitably skewed by that.